SWIM Protocol explained

25 Mar 2017 | distributed-systemsIn this post I will describe SWIM, a well known gossip-based membership protocol. before diving into SWIM specifics, it’s probably a good idea to start with a quick overview of membership protocols and the problem they attempt to solve.

Membership Protocols

Imagine a group of members (processes) who communicate among themself over a network. The group is dynamic; members can appear and disappear at any time. Membership protocols try to answer a simple question: from the point of view of each server, who are my live peers?

Of course, as we deal with an unreliable network, we should expect and handle packet losses, transmission delays, network partitions and so forth.

Membership protocols have many use cases in all kinds of distributed systems, such as Peer-to-peer file sharing networks, network overlays and distributed databases.

SWIM Protocol

SWIM full name is Scalable, Weakly-Consistent, Infection-Style, Processes Group Membership Protocol. Lets break this down:

By scalable we mean that the protocol is applicable for large networks, consistings of thousands or tens of thousands of nodes. When dealing with networks of this magnitude, we must take into consideration the amount of messages sent among the nodes.

By Weakly Consistent we mean that each node will have a somewhat different view of its surrounding environment. Over time, as nodes communicate and exchange information, we expect these conflicting views to converge.

Infection Style is a synonym for gossip. Each node is expected to exchange information with a subset of its peers, so information flows in the network similar to the spread of an epidemic in the general population.

Lastly, Membership Protocol means that we expect SWIM to answer the basic question - who are my live peers?

Heartbeats Limitations

Prior to SWIM, most membership protocols used a method called heartbeats; Each node

periodically sends a HEARTBEAT message to all other nodes in the network, indicating to them that it’s alive. If a node does not receive a

heartbeat for some predefined interval, the peer that should have sent the heartbeat is assumed to be dead. This method guarantees that any

faulty node will be detected by any non-faulty node.

While heartbeats works quite well for small networks, it has a problem to scale because of the network load: as each node sends a message to every other node, the total amount of messages is every interval for network with size . Clearly this is impractical when N grows to tens of thousands of nodes.

SWIM takes a different approach; it separates the failure detection operation from that of membership update dissemination. In other words, SWIM demonstrates that by loosing up the requirement for failure detection we can dramatically decrease the network load.

Failure Detection

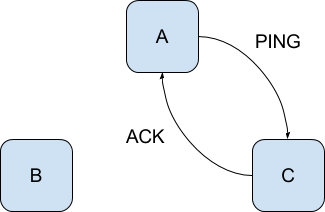

SWIM uses two parameters: T, which is the protocol period time, and k, the size of failure detection subgroup. In each period, each node

randomly selects 1 peer (assume for now that a node is already aware of its peers) and sends a PING message to it. Once a node receives a

PING message it responds to the sender with an ACK message, indicating that it is healthy.

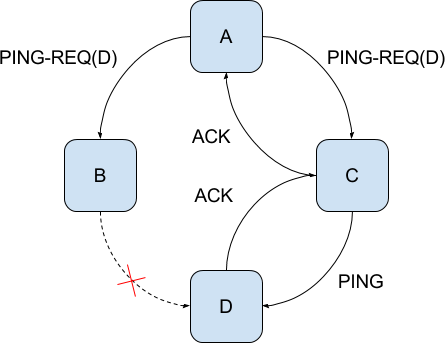

If a ACK is not received within some predefined time span (determined by the message round-trip time, but smaller than the period time),

the node switches to indirect ping; It randomly selects k other peers and asks each one of them to ping the suspicious node and forward the

ACK back. Only if a node hasn’t received neither the original ACK not any of the k indirect ACKs it assumes a peer is dead.

We’ll skip the mathematical analysis (it is presented in the paper), but this technique essentially lowers the asymptotic amount of messages in the network from to , which is much more reasonable amount.

Information Dissemination

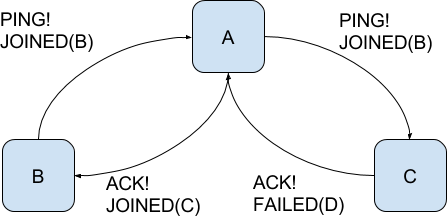

the information dissemination component is used to maintain the list of peers that each node knows. There are 2 types of messages used:

JOINED and FAILED.

JOINED(P)is sent by nodePwhen it first joins the network. Any node receiving this message will addPto its list of peers.FAILED(P)is sent by a node when it detectsPis faulty, as explained above. Any node receiving this message will removePfrom its list of peers.

To make information dissemination more efficient, we piggyback these two messages on top of the PING messages that each nodes already

sends to its peers.

Once again, we’ll skip the analysis but the bottom line is that it takes time for information to spread in the entire network.

Comments